Over the past twenty centuries, the Catholic Church has experienced and expressed its worship in various ritual forms that, while retaining its essential elements, has seen its expression evolve in a dynamic way. Alongside this healthy, organic environment has been a corresponding development in the architectural forms whose purpose is to visibly express the celebration of these mysteries in relation to the sanctification of the Church and the world.

From Sunday Evening Meal to Sunday Morning Worship

In the early Church, Catholics first met in homes to celebrate the Eucharist (Acts 20:7-12), the memorial of Christ’s Passover. Initially, this sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving was actually coupled with a meal (1 Cor. 11:17-31/Acts 2:42; 2:46). Later, scripture readings replaced this ordinary meal held prior to the memorial meal described in Scripture as “the breaking of bread” (Acts 20:7; 11). This was an accomplished fact by the beginning of the second century. Once the Eucharistic sacrifice was separated from the regular meal, the Christian community began to celebrate the Eucharist in the early Sunday morning hours as opposed to Sunday evening. This was a reminder that the Lord had risen in the early hours of the first day of the week.

Notice how preaching, the “breaking of bread” and concern for one’s neighbor are intimately linked in the following account given by Saint Justin Martyr of how Christians around the year 150 A.D. celebrated the Eucharist … “And on the day which is called after the sun, all who are in towns and in the country gather together for a communal celebration. And then the memoirs of the Apostles or the writings of the Prophets are read, as long as time permits. After the reader has finished his task, the one presiding gives an address, urgently admonishing his hearers to practice these beautiful teachings in their lives. Then together with all stand and recite prayers, as has already been remarked above, the bread and wine mixed with water are brought, and the president offers up prayers and thanksgivings, as much as in him lies. The people chime in with an Amen. Then takes place the distribution, to all attending, of the things over which the thanksgiving had been spoken, and the deacons bring a portion to the absent. Besides, those who are well-to-do give whatever they will. What is gathered is deposited with the one presiding, who therewith helps orphans and widows.” (First Apology, Chapter 67)

Bonding the Faithful and the Community of Saints

During periods of intense persecution, large numbers of the faithful celebrated the Eucharist on the feast days of martyrs in the various catacombs in and around Rome. It was common to use sarcophagi (stone coffins) for altars during these Christian services. A relic of our patron Saint John Neumann is placed in the mensa (altar top). According to Antonio Baruffo, author of The Catacombs of Saint Callixtus, “the catacombs can be regarded as the cradle of Christianity and the archives of the primitive Church. Their paintings, sculptures, and inscriptions provide the most valuable material for illustrating the usage and customs of early Christians and the history of the persecution they suffered. Moreover, they enable us to show how identical was the faith lived in the first centuries with the Act of Faith, or Credo, that we profess today. This has great value for us because these monuments, the catacombs, belong to the first centuries of Christianity. It is undeniable that Christian archeology can give, for some truths of the Catholic faith, proofs in the proper sense, for instance, judgment and reward after death, the communion of saints, the efficacy of prayer of the living for the dead and vice-versa, the existence of purgatory, the cult of the holy martyrs, the coming of Saint Peter to Rome and his pre-eminence in the Church, and the very ancient use of the sacraments, such as Baptism and the Eucharist.” Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2000

Making More Room

Once the persecution of Christians was no longer the norm, due in large part to Constantine and the Edict of Milan, the Church began to accommodate a larger number of worshipers by constructing and worshiping in larger buildings modeled after the classical Roman architectural style.

The first such structure was Saint John Lateran in the city of Rome around the year 313. This church may still be visited today. For Christians, freedom of worship gave way to a privileged status in the latter part of the fourth century and Christians continued to build, gather, and worship in sacred spaces.

As early as the fifth century, church architecture changed from the classical Roman style to the Byzantine style, with its beautiful iconography, decorated domes, marble columns, pendentives, and mosaics.

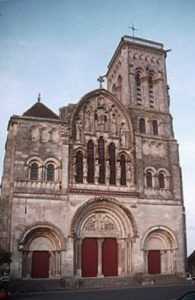

Toward the close of the first millennium, the Romanesque style appeared with its rounded arches, heavy columns, large towers, and thick walls. This style was characterized by simplicity in comparison to the Gothic style into which it evolved.

This latter style was characterized by its pointed arches and flying buttresses and lasted another four centuries. From the end of the sixteenth century, well into the eighteenth, we find the Baroque style with its emotional and sensory appeal. This was immediately followed by the neo-Gothic movement/style that continued into the early part of the twentieth century.

The Romanesque style had its own short-lived revival beginning in the nineteenth century.

Since the Byzantine era, these various architectural styles all had one thing in common – they were built in the *shape of a cross. Soon after World War II, however, this cruciform shape gave way to a modern architecture style which did not concern itself with any of the traditional ecclesiastical architectural components. Whatever the rationale for such a dramatic shift, there is no question that this modern architectural style was not consistent with the organic development which permeated previous architectural designs.

The design for Saint John Neumann is intentional. A Catholic Church building should speak, sometimes subtly, at other times forcefully, about the truths and the mysteries which are celebrated within its walls. Such is the case with Saint John Neumann Church. At the dawn of the third millennium, we hope that Saint John Neumann Catholic Church can make a contribution to the repositioning of church architecture to its rightful place, by expressing in a dynamic and awe-inspiring way, the role of the liturgy in the Church and the Church in the world.